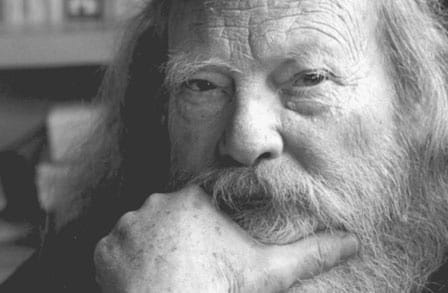

I had never heard of Hayden Carruth (1921-2008) until I read this poem this morning. Indeed, I wrongly assumed that Hayden was a woman. I now know that he was a prolific and successful American poet influenced by jazz and blues, a tenured professor, and poetry editor of Harper’s (a favourite magazine of mine) who lived for many years in Vermont. I like the title of one of his best known poetry collections: Scrambled Eggs and Whiskey. I’m tempted to buy a copy based simply on the title and reading one poem by Carruth.

The author Jonathan Franzen selected this poem for an anthology that I’m reading, and his one comment was that the line “They are going away” got him every time. That line is the heart of the poem. Wild animals are disappearing fast, being replaced by humans and animals bred for humans to eat.

This morning I’ve been reading as well the biologist E O Wilson’s classic book The Diversity of Life. The lyrical book makes the case for biodiversity in that the more species we have the more able nature will be to adapt to whatever happens to the Earth–nuclear Armageddon, great heating, explosion of a megavolcano, or a strike by a meteor. In the chapter I read this morning Wilson describes what happened as nature returned to Krakatua after the 1883 explosion had rendered it to nothing but hot rock. In short, a century after the explosion the tropical forest on the island was similar to that of other Indonesian islands.

Creatures arrived by air, sea, raft, and by hitchhiking rides.

As I read Wilsons’ list of the invertebrates found on the island a century after the explosion, I wondered about converting it to a found poem–but it’s too much of a list. Instead, I tie the paragraph together with Carruth’s poem.

“A large host of invertebrate species, more than six hundred in all, lived on the island. They included a terrestrial flatworm, nematode worms, snails, scorpions, spiders, pseudoscorpions, centipedes, cockroaches, termites, barklice, cicadas, ants, beetles, moths, and butterflies. Also present were microscopic rotifers and tardigrades and a rich medley of bacteria.”

Carruth writes of the animals leaving, Wilson of nature returning. I should point out, however, that if we destroy all vertebrates on the planet they will not be back within a century. It will take tens of millions of year for equally complex, beautiful, and capable creatures to emerge.

Essay by Hayden Carruth

So many poems about the deaths of animals.

Wilbur’s toad, Kinnell’s porcupine, Eberhart’s squirrel,

and that poem by someone–Hecht? Merrill?–

about cremating a woodchuck. But mostly

I remember the outrageous number of them,

as if every poet, I too, had written at least

one animal elegy; with the result that today

when I came to a good enough poem by Edwin Brock

about finding a dead fox at the edge of the sea

I could not respond; as if permanent shock

had deadened me. And then after a moment

I began to give way to sorrow (watching myself

sorrowlessly the while), not merely because

part of my being had been violated and annulled,

but because all these many poems over the years

have been necessary–suitable and correct. This

has been the time of the finishing off of the animals.

They are going away–their fur and their wild eyes,

their voices. Deer leap and leap in front

of the screaming snowmobiles until they leap

out of existence. Hawks circle once or twice

around their shattered nests and then they climb

to the stars. I have lived with them fifty years,

we have lived with them fifty million years,

and now they are going, almost gone. I don’t know

if the animals are capable of reproach.

But clearly they do not bother to say good-bye.

Leave a comment